STAT 4194 @ OSU

Spring 2019 Dalpiaz

The Extended Syllabus | STAT 4194 | OSU | Dalpiaz

The Extended Syllabus

The following are some of my thoughts on teaching and learning. These include some teaching philosophy, reasoning behind course policies, and general suggestions for student success.

Perhaps you will find some of these thoughts useful. My hope is that by keeping some of this information in mind, we can have a successful semester learning from each other.

Over time I will likely update this document to be better organized, better written, more general, and more useful. (It was hastily written for the first time for the Autumn 2018 semester.)

Course Goals

In addition to the specific learning objectives of any course, I approach each class with three additional, more broad goals.

After each class I teach, I hope that students have learned to…

- Be a better statistician.

- Be a better programmer.

- Be a better learner.

That last item is the most important.

- TODO: This section needs expanding.

Good Faith and Trust

Often, when you first meet someone, you don’t necessarily trust them. Trust is something that is built over time.

Unfortunately, this is a bit of a problem when a course is only a short, finite amount of time. For this reason, I believe it best that you assume that I am operating in good faith. I will extend the same courtesy in return.

Essentially, we should quickly come to the agreement that we have the same goals. You want to learn the course material, and I want you to learn the course material. (I also have some additional goals outlined above, that hopefully you share as well.)

Sometimes students have some additional, more short-term goals such as completing an assignment, or obtaining a desired grade. While I am sympathetic to these goals, they do not directly match mine. I hope to teach you well enough that you are able to complete your assignments. I hope to teach you well enough that you are able to obtain good grades. This difference is subtle, but important. If my goal was to simply have you complete all your assignments, I could just give you the answers. If my goal was for everyone in the class to get an A, I could simply give everyone an A. However if I did these things, I would be working against my goals of helping students learn.

Grades

In many ways grades are an unfortunate reality of the education system. I thought I disliked them as a student, but now as an instructor, my dislike has only grown. Alas, we exist in a system with grades, so we’ll have to make the most of it.

This is simply my opinion, but I believe that grades are a function of roughly three things:

- Prior Knowledge

- Effort

- Luck

That is,

\[ \text{grade} = f(\text{prior knowledge}, \text{effort}, \text{luck}) \]

I don’t know precisely what that function \(f\) is, but I think the inputs and outputs are the correct variables. I think it is helpful for both parties involved, students and teachers, to think about what control they have over each of the inputs.

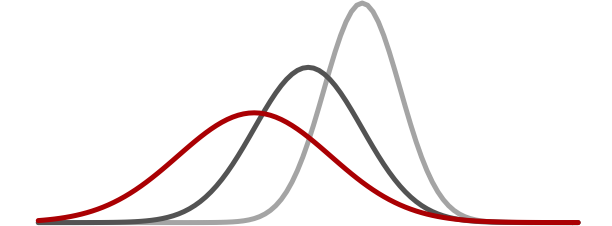

As students, you generally have very little control over prior knowledge. In many cases this amounts to taking a prerequisite course. (Hopefully you have!) While it would be great if you had full understanding of the material of any prerequisite course, I understand that there will be a wide variance among students. And even if I could assume that all students had a perfect mastery of a prerequisite course, there are certainly many other prior experiences that could prove helpful in a course. As a result, dealing with prior knowledge is mostly my responsibility. Often the best I can do is to simply be understanding of the fact that students have a wide variety of past experiences. Obviously I will do my best to help you review and recall important information from prerequisite courses. And I will always be available in office hours to help overcome any shortcomings stemming form some missing knowledge. (Within reason of course. As much as I would like to try, I can’t teach an entire prerequisite course during office hours.)

Effort is generally the input that students feel they have the most control over. However, I often feel that students believe that blinding putting forth effort will result in high marks. I think it is more appropriate to say that properly applied effort will lead to high marks. Grades aren’t given for effort, they given for mastery of materials, it’s just that you can’t master the material without the effort. Students generally find it difficult to understand where they should place their effort. In any particular course I will be happy to provide some concrete examples, but as a general heuristic, if you don’t find yourself “failing,” then you aren’t putting forth the correct type of effort. For example, reading the textbook to study for an exam might seem like you are putting forth effort, but in reality, this is not a good use of time. Reading the textbook is passive, and there isn’t really a way to fail. Instead, consider doing practice problems. (No cheating and looking at the solutions first.) Each problem you do is an opportunity to fail, thus identifying for yourself where you need to focus your time and energy. As an instructor, I do have some control over effort, mainly though the amount of homework, labs, exams, and projects that are assigned. I try best not to abuse this power, and try to keep these activities to a reasonable level. However, I do make an attempt to have at least one of these activities each week. Often consistent effort is better than sporadic bouts of heroic effort.

I believe that the part of grades that students often ignore is luck. It may sound strange for an instructor to admit that luck influences a grade, but I do believe this is extremely important to acknowledge. Suppose Student A and Student B are equal in every conceivable way. The night before an exam, Student A studies for two hours, then sleeps for eight hours. Student B had set aside two hours to study, but at the last minute, a phone interview for an important job comes up. This ruins Student B’s plans for the day. Student B gets to the library later than planned and only gets in an hour of studying, then also gets home late and only manages seven hours of sleep. Student A performs better than Student B on the exam. Does Student A actually know the material better than Student B, or are they just lucky? You can probably think of a million little things like this. Uncertainty is a part of life. The only way for you to counteract situations like this is to be as prepared as possible as early as possible. It’s not always possible to study for an exam a week in advance, but if you plan to do all your studying the night before, you’re running a huge risk. While this might sound like a potentially unfair situation, and at first glance I agree, I am comforted by the statistical reality of the situation. By having enough (uncorrelated) assignments in a class, the signal will overcome the noise. More on this in a later section.

All of that said, with some careful planning and execution, I believe that grades generally reflect how well a student has learned.

Grades As Estimation

- This section will be updated later after we learn the necessary course material. The explanation here requires an understanding of some of the course concepts!

Grading Disputes

Please do not view the grade dispute policy solely as an attempt to diminish discussion of grades. While it does create certain logistical advantages for the course staff, in reality, a large driver of this policy is to encourage students to evaluate their work against the given solution and to seek additional individualized feedback. The sooner this occurs, the greater the benefit.

This policy will also help students keep better track of their grades. The grade “dispute” that actually occurs most often is a result of entry error! The course staff is human after all, and mistakes are most likely to occur when adding up points, or entering a grade into a computer. Fixing these makes earlier rather than later is best for everyone.

Email Communication

Email is a blessing and a curse. Instant communication is wonderful, but often email is the wrong medium to have a productive conversation about course material. Asking questions about course material is always best done in-class. Students always roll they eyes when instructors say it, but it’s true that if you have a question, it’s very likely someone else has the same question. (An alternative here would be a message board if the class is large enough, but again, in-class is still the best option.) The next best place to ask a question, or if you need some more individualized feedback the best place to ask a question, is office hours. Instead of being limited to a single email replay (or letting an email thread drag on for hours or days) the feedback loop can continue immediately.

- TODO: Introduce the idea of “communication bandwidth.”

That said, email is still useful. If you’re going to use it, you should at least use if effectively. There’s a running joke in academia that professors only read an email until they find a question. They then respond to that question and ignore the rest of the email. I won’t do this, but I do think it is helpful to assume that the person on the receiving end of an email will operate this way. By keeping this in mind, you will write a much more concise and easy to understand email.

Some general tips:

- Use your University supplied email for University business. This helps me know who you are!

- Use a short but informative subject line. For example: [STAT 3202] Project Dataset

- One topic, one email. If you have multiple things to discuss, and you anticipate followup replies, it is best to split them into two emails so that the threads do not get cluttered.

- Ask direct questions.

- If you’re asking multiple questions in one email, use a bulleted list.

- Don’t ask questions that are answered by reading the syllabus! If you do, you’ll probably get a reply that is simply a link to the syllabus! :)

I’ve also found that students are overly polite in emails. I suppose it may be intimidating to email a professor, and you should try to match the style that the professor prefers, but I view email for a course as a casual form of communication. Said another way, get to the point! Students often send an entire paragraph introducing themselves, but if you use your University email address, and add the course name in the subject, I will already know who you are. Here’s an example of a perfectly reasonable email:

Subject: [STAT 3202] Homework 3, Question 4, Typo

Hi Dave,

There seems to be a typo in Homework 3, Question 4. The problem says Poisson, but the given mass function is for a binomial. Which should we use?

Thanks,

Your-name-hereOffice Hours

I have often found that student have not been taught how to best utilize office hours. Actually, worse yet, I find that many students don’t even bother to consider using office hours! If that’s you, please do stop by if you need some help.

To understand how to best use office hours, it helps to understand my goal during office hours; helping students learn. To achieve this goal, it is first necessary to understand what a student does and does not know. This requires some back-and-forth, and I often end up asking more questions than I answer. Some students find this frustrating. Other students find this intimating. I’m understanding of both of these feelings, but please realize that we are working towards the same goal. By questioning you, I am not testing you, or trying to make you look bad. I’m try to understand what I can do to help. I’m also trying to lead you down a path to solving a problem yourself.

When being questioned (for lack of a better phrase), please resort to using “I don’t know” as an answer as little as possible. This doesn’t help the process. It is much more useful to give an incorrect answer so we can discuss why it is incorrect. Also, if you provide a correct answer, expect the follow-up question: “Why?” Being correct is good. Being correct with confidence is better.

- TODO: This section needs expanding.

Health

If you’re reading this document, it is most likely the beginning of the semester, and you are feeling physically refreshed and mentally relaxed compared to the end of a semester. To have the most successful semester possible, you should strive to keep that feeling as long as possible. Please consider taking the time during the semester to stay happy and healthy. Three things that go a long way:

- Diet

- Exercise

- Sleep

You don’t need to eat some sort of super strict diet, but maybe not pizza and beer every night.

I’m blown away by the Recreational Sports facilities at OSU. Please don’t let them go to waste.

I understand that students live in dorms, and sometimes there are a lot of barriers to sleep. Don’t let noise be one of them. Earplugs are very cheap and very effective, if worn correctly.

- TODO: This section needs expanding.

Academic Integrity

I genuinely enjoy my job. However, there is one part of the job that I truly loathe: dealing with academic misconduct. While I view assigning grades as a minor annoyance, at least the act of grading is coupled with providing student feedback, which is extremely important to learning. Dealing with academic misconduct is nothing but a time-sink that detracts from the goals of teaching. I offer students two pieces of advice:

- Cheating is much easier to detect than you realize.

- If you feel like you might be operating in a grey area, you probably are.

I certainly understand that there can be extreme pressures to obtain good grades. My hope is that instead of resorting to extreme measures such as academic misconduct, that instead, a student would seek help in office hours as early as possible.

Life Advice

Life advice is in no short supply. Self-help books make up huge sections of bookstores. (Or at least they did when bookstores were still popular.) But in terms of general advice that is always applicable, one phrase has always stuck with me:

“Show Up, Don’t Quit, Ask Questions”

I don’t know the source, but I first heard it from the a Strength and Conditioning coach named Dan John. (He claims to have stolen the idea, but can’t remember who he stole it from.)

While I think this applies to accomplishing just about any goal in life, I think it is particularly applicable to academic success. Some brief explanations:

- Show Up: “Showing up is half the battle.” If in addition to attending class, you extend this to doing homework, labs, etc, I think it might be 90% of the battle.

- Don’t Quit: It’s a long semester. There will likely be ups and downs. Don’t let that affect your attitude or effort.

- Ask Questions: You know what you don’t know better than anyone else. Get your questions answered!

Unknown Unknowns

“Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

– Donald Rumsfeld, United States Secretary of Defense

While the presence or lack thereof of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq isn’t particularly important to teaching, this response from Donald Rumsfeld at a Department of Defense briefing popularized the ideas of known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns. I find these classifications to be useful for thinking about learning.

When you start a course, pretty much everything is an unknown unknown. In other words, at this stage of the course not only do you not know the material, but you also don’t know what material you need to know.

The next stage comes after lectures or readings. At this stage you are beginning to acquire known unknowns. You’ve now been introduced to the materials, but you still do not know them. This is an important point. Attending lecture or reading a book are required for learning, but not truly where learning takes places. Would you want to take an exam based only on attending a couple lectures?

To move from a known unknown to a known known you have to engage in the course activities, in particular activities that generate feedback. You do practice problems then check the solutions. You turn-in a homework and get feedback from the grader. You come to office hours to get a specific question answered.

See One, Do One, Teach One

Much of surgery is taught via the “see one, do one, tech one” method. While this sounds terrifying from a patient perspective, I think they’re on to something, in particular with the “do” and “teach” parts. The “do one” part aligns nicely with the idea of moving from a known unknown to a known known. (See above.) Having taught for a while now, I’m finding it increasingly true that you don’t truly know something until you can explain it to someone else. I’m not suggesting that every student go out and become a professor so they can teach a subject in order to learn it, but if you see an opportunity to help explain something to a classmate, do it!

See Something, Say Something

I create a lot of my own course materials, however, I do not have an editor. Try as I might, proofing your own work is difficult, so typos slip though. Often, they are so obvious that no one let’s me know about them. Don’t do that! Send a quick email to let me know! (There’s probably a typo in this document. Did you find any? Let me know!)